Relationships frequently become dry or even break down

because people don’t express the affection they have for each other. As finite

beings, we can’t read others’ minds. So only when our loved ones express their

feelings for us do we feel reassured that our feelings are reciprocated.

But expressing emotions is not the only way to show love.

Sometimes, love may be shown best by concealing emotions. If a child is going

to a distant land for higher studies, the mother may feel overwhelmed by

anxiety. Yet she may conceal her tears so that her child has a happy last

memory of a proud parent offering good wishes and blessings.

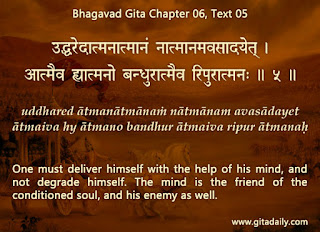

The essence of love is not emotions, but purpose: the

purpose of doing the best for our loved ones. Such a purpose-centered

understanding of love illumines the Bhagavad-gita’s exhortation (12.17) to stay

equipoised amidst happiness and distress, which may seem like a call for

unemotionality. Paradoxically, this same verse states that such equipoise among

devotees endears them to Krishna.

Why does unemotionality please Krishna? Because it helps us

focus on him. Presently, because we are materially attached, most of our

emotions are about temporary material things, and when we let such emotions

carry us away, we lose sight of our long-term spiritual good.

In bhakti-yoga, we demonstrate our love for Krishna by both

expressing appropriate spiritual emotions whenever we feel them and

subordinating those emotions that obstruct our spiritual purpose. For example,

on a holy fasting day, we may not like to fast. But instead of spending the

whole day with a sullen face, we strive, as an austerity, to absorb ourselves

in serving Krishna as cheerfully as possible.

When we cultivate such absorption by concealing

inappropriate emotions, we become purified and gradually relish constant spiritual

emotions.