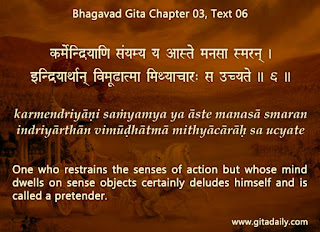

When we strive to live according to some elevated

principles, there results an inevitable tension between our precepts and our

practices. The level that we live at rarely rises to the level we espouse and

expound. The tension between the two can spur us to raise ourselves up, to

start striving strenuously to practice what we preach. Even if we are unable to

do so, just the sincere aspiration will keep us on the path to

self-improvement. Unfortunately, we may succumb to the mind’s trap of

compartmentalization. That is, the mind may compartmentalize our public

comportment and our personal conduct into two water-proof compartments, where one

has no bearing on the other. The mind makes us believe that as long as we can

maintain the facade of being priniciple-centered , it doesn’t matter if we in

our private life are actually pleasure-centered, not principle-centered. The

Bhagavad-gita (03.06) cautions about such a disjoint when it reproaches those

who put on the garb of renunciates but internally contemplate on sense objects.

Interestingly, the Gita refers to such people as not just hypocrites, but also

as self-deceivers. They may or may not fool others, but they are fooling

themselves. By imagining that they can get away with just the facade, they are

depriving themselves of the substance of spirituality – the sublime

satisfaction that comes by being able to steadily absorb oneself in the remembrance

of Krishna, who is the source of all happiness. In today’s cultural ethos, such

compartmentalization has become accepted as a routine fact of life. If the

President keeps the economy on the growth track, what scandalous affairs he has

in his person life is his own business – so goes the mind’s deceptive mantra, a

mantra that the mainstream media has adopted as its own. Amidst such a cultural

setting, we need to know that the process of bhakti is choked by the mind’s

compartmentalization approach. Krishna needs to permeate and conquer our entire

being – external and internal, in fact, the internal is more important than the

external. By seeing the mind’s compartmentalization mechanism as

self-deception, we can reject it and progress towards self-realization and

devotional culmination the supreme satisfaction of pure love.

Tuesday, 31 May 2016

Friday, 27 May 2016

Money is one measure of value, not the only measure of value

We live in a materialistic, money-centered culture that is

almost mercenary in its obsession with money. Money is essential for our

survival, so it is a measure of value. But it is not the only measure of value.

That is, there are things whose value transcends money, whose value can’t be computed

in monetary terms – for example, the love of our loved ones and ultimately the

love of Krishna. When people value money more than relationships, then they

sentence themselves to loneliness because they become suspicious of everyone

around them. Money can make people not just suspicious, but also malicious –

not only do they dread that others will harm them for the sake of money, they

themselves may decide to harm others for its sake. The Bhagavad-gita (16.13-15)

states that such people get so consumed by schemes for making money that their

ethics and even their humanity gets consumed. They don’t feel any compunction

in planning the elimination of those who obstacles on their path of monetary

aggrandizement. Of course, most of us will never go to such horrendous extremes

in the pursuit of money, but we need to recognize the deadliness of the

slippery slope down which infatuation with money can push us. When we practice

bhakti and understand the Gita’s revelation about the nature of reality, we see

that the ultimate value of money lies in its capacity to be used in the service

of the one who is ultimately valuable, the one who alone is going to remain

with us when times takes away money and everything else of value. By giving the

supreme value to Krishna, we can give appropriate value to money and ensure

that we use it in a way that it adds value to our life, not subtracts value

from it.

Wednesday, 25 May 2016

Don’t just talk about yourself – talk to yourself

People who like to talk about themselves can come off as

egotistic when they describe their successes and as whiners when they explain

(away) their failures. Undoubtedly, when reversals are caused by factors beyond

our power, we may need to clarify things, which might require talking about

ourselves: our situations and limitations. Nonetheless, we can often better do

things that are in our power to do by talking to ourselves – that is, by urging

ourselves to improve ourselves. For example, during vital phases of play, some

sports players galvanize themselves with self-exhortations: “Come on,” “Buck

up,” “The time is now.” Taking such self-talk beyond pep talks to philosophical

introspection, the Bhagavad-gita (06.05) suggests that we create a

self-reflective difference of subject and object within ourselves when it urges

us to elevate the self with the self. While some commentators translate the

instrumental self here as the mind, others stick to the literal import of the

word ‘atma’ as self. With the direct reading, this Gita guideline channels one

of our deepest tendencies: to give advice to others. By treating ourselves as

the other, we can give advice to ourselves. This self-talk is neither the

irrational self-obsession of the lunatic, nor the unconsidered chatter of the

wild-minded. It is the mature, measured, focused introspection of those who

first internalize scripture and in its light observe themselves, evaluate their

actions and encourage themselves to do better. Unlike the public, effusive

self-exhortations of sportspersons, spiritual seekers, who strive to improve

their inner terrain, often prefer more private, restrained forms of

self-counseling. Journaling is one such way, wherein we talk with ourselves on

paper, thereby bringing greater objectivity and longevity to our self-talk. By

adopting the self-talk we find most helpful, we can progress towards

self-improvement, thereby finding increasing satisfaction within and making increasing

contribution without

Tuesday, 24 May 2016

Regulation is a protection measure, not a trust issue

Suppose a teenager is to stay alone at home. When his

parents are leaving, they remind him to bolt the door and activate the security

system. But, with typical adolescent machismo, he bristles, “Don’t you trust

me? I can fight off any thieves. Just see my biceps.” Closing doors is not a

trust issue, but a protection measure. What if several thieves come in – or if

they come armed? Why risk unnecessary danger? Today’s Internet-based digital

culture offers us round-the-clock access to a whole universe of distraction.

Such distraction threatens our basic concentration and contribution, and even

our ethical and moral standards. Moreover, with the proliferation of

unsolicited mails, deceptive links and pop-ups, we may find ourselves transported

digitally into triviality or obscenity without even realizing where we are

going. Pertinently, the Bhagavad-gita (03.41), while outlining how to combat

lust, recommends that we begin by regulating our senses. Regulation of senses

means not just regulating sensual indulgence, but also regulating access to

opportunities for such indulgence. Translated to the digital domain, this Gita

recommendation can mean regulating net access through appropriate filters. When

our well-wishers recommend such regulation, we may take offense and ask, “Don’t

you trust me?” Actually, that’s the wrong question to ask because the issue

here is not trust, but protection. We gain nothing except danger by keeping a

door unnecessarily open in our digital domain. Even if we can resist

distractions, we have better things to do in life than fighting avoidable

distractions. The best thing we can do, Gita wisdom explains, is to learn to

love and serve Krishna, thereby progressing towards meaningful contribution in

this life and ultimate liberation in the next. By voluntarily closing the door

to non-devotional and anti-devotional alternatives, we give ourselves

opportunities for deeper absorption in constructive service to Krishna.

Saturday, 21 May 2016

What we don’t have is not the problem – what we don’t see is

We frequently crave for the many things we don’t have,

things often aggressively glamorized by today’s corporate controlled media.

Such greed and its concomitant dissatisfaction are, the Bhagavad-gita (14.12)

indicates, characteristics of the mode of passion. Greed is like a malaise

afflicting our psyche. As long as we are thus afflicted, satisfaction will

elude us, no matter how much we acquire; greed will make us dissatisfied about

not having some other thing. To cure greed most effectively, we need to

practice the potent purificatory process of bhakti-yoga. This yoga makes us

aware of the indwelling presence of Krishna, who is the all-attractive,

all-loving, all-joyful Absolute Truth. We are his eternal parts. Absorption in

his remembrance enriches us far more than the best external acquisitions. The

Gita (06.22) assures that the topmost yogis who relish the highest spiritual realization

feel so satisfied that they don’t crave for any other gain. However, the same

dissatisfaction that dogs us in our material life can distract us in our

spiritual life too. To gain the intellectual conviction for focusing on

Krishna, we need to recognize our real problem, the root cause of our

dissatisfaction: our inability to see what we have, both materially and

spiritually. Materially, if we contemplate the talents and assets we do have

and look not at those who have more, but the many who have less, we can curb

our dissatisfaction. Spiritually and more importantly, we can contemplate our

immeasurable spiritual treasures: Krishna’s indwelling presence, and the

opportunities to practice bhakti-yoga for relishing that presence. Dwelling on

what we have will engender contentment and enable us to work with a higher

motive – not the insatiable craving for more, but the aspiration to do justice

to our God-given gifts and to share the process for inner enrichment.

Thursday, 19 May 2016

To see differences as fundamental and final is delusional

Across the world, we see a staggering variety among people

in races, castes, classes, religions and nationalities. Such differences often

trigger conflicts. But they don’t have to. Why not? Because such differences,

though real, are neither fundamental nor final. Those differing attributes do

not emerge from their fundamental being. At their core, they are essentially

like us – they too are souls. They are people like us who too seek pleasure and

avoid pain, who too dream and worry and work and laugh and cry, who too long to

love and be loved. The Bhagavad-gita (18.20) indicates that seeing this

essential commonality and spirituality of all is perception in the mode of

goodness. In contrast, the next verse (18.21) characterizes as perception in

the mode of passion the notion that differences in bodily forms and features

represent differences in essential natures. Just as the differences between

people are not fundamental, they are not final either. That is, the features in

which they differ from us are not their unalterable attributes. Actually, to

deem those attributes as irreversible, irredeemable definers of character is a

foundational delusion, for to reduce people to their bodies is the foundation

of delusion (02.11). So, when we label some group of people as dumb or some

other group as terrorists just because some, even many, people in that group

display those characteristics, we betray our own spiritual ignorance. By

internalizing Gita wisdom, we can defuse many triggers of conflicts. Further,

if we share spiritual wisdom with others, we can empower them to connect with

the whole – of whom they too are parts, as are we (15.07). The more we all

avail of the illumination coming from that divine connection, the more we can

manifest our pure spiritual potential, thereby living in a sublime harmony that

transcends divisive sectarianism.

Wednesday, 18 May 2016

Walking away from problems is not the same as running away from them –

When we are driving for an important and urgent meeting, if

someone cuts ahead of us, we may decide not to chastise or sue that person

because we want to reach our meeting on time. Similarly, many of life’s

problems are not worth fighting. If we are ruled by a macho man attitude, then

we may think of turning away from problems as a cowardly running away. But not

all turning away is running away – some of it can be walking away. The

difference between the two is often a difference of attitude and purpose. When

we run away from a problem, our consciousness is consumed by the scariness of

the problem and our inability to deal with it. Our only concern is to somehow

run for refuge somewhere, where it doesn’t matter, as long as it is away from

the problem. When Arjuna recoils from a gruesome war with his relatives,

Krishna reproaches him by reminding him (Bhagavad-gita 02.35) that his enemies

will deem his actions as a cowardly running away. But the same Gita recommends

walking away when it (06.11) recommends that yogis renounce the world and go to

a secluded place for practicing meditation and striving for liberation. We can

walk away not just by physically distancing ourselves from irritants, but also

emotionally turning away from them. The Gita (02.14) recommends such emotional

distancing when it urges Arjuna to tolerate the unpleasantness caused by life’s

dualities. When we walk away from problems, either physically or emotionally,

we focus on what we are moving towards, not what we are moving away from. That

positive focus makes walking away not spinelessness, but mindfulness – a

hard-eyed discretion that enables us to put first things first, thereby

clearing the way for our significant successes. –

Monday, 16 May 2016

In the truth of who we are and what we love lies our deepest fulfillment

We all desire lasting life, lasting love and lasting

happiness. We expect certain things from those whom we love and feel

disappointed when they don’t live up to our expectations. Actually, these

aspirations can be fulfilled not by acquiring something external or finding

some elusive person in some corner of the world to love. Yes, some such things

may be better than other, but none can fulfill our deepest longing. Our

aspiration can be fulfilled by going inwards to understand who we are and act

according to the truth of our identity. In the truth of who we are — eternal

souls who are parts of Krishna, as the Bhagavad-gita (15.07) states — lies the

origin of our deepest longing. And in truth of what we love — that is, in the

true understanding of who is the truest object meant for our love, we can move

closer and closer towards the elusive happiness that we are looking for. The

Gita (18.54) states that when we realize our spiritual essence, we become free

from the worldly cravings and frustrations that characterize our life at the

material level of consciousness. By finding satisfaction in our spiritual

identity and glory, we become free from dependence on outer pleasures and thus

become free also from vulnerability to the misery that comes from loss of those

pleasures. And in that purified state of spiritual realization, we direct our

love fully towards Krishna, not for getting something from him at the material

level of reality, but because we recognize him that he is the embodiment and

fulfillment of our deepest aspirations, that he is his greatest blessing and

that he gives himself to us by his sublimely relishable self-revelation when we

learn to love him purely.

Friday, 13 May 2016

Focus not on freedom — focus on love

Today’s culture often enthrones freedom as the highest good,

as an absolutely inviolable tenet. Undoubtedly, freedom is one of our innate

longings, and it needs to be protected. Yet in our idealization of freedom, we

shouldn’t forget that freedom is itself not the ultimate end — it is a means to

some higher, nobler purpose. The purpose that brings us the deepest fulfillment

is love: we all want to love and be loved. And forming any kind of loving

relationship requires subordinating freedom to love. When two people get

married, they give up much of the freedom they may have earlier had to dally

with others so that they can deepen their mutual relationship. Similarly, when

a mother has a baby, her freedom is often curtailed by the need to care for the

baby. But the love inherent in such caring brings a profound fulfillment that

freedom alone can’t. If we approach spiritual life and bhakti-yoga with

freedom-centered spectacles, we may find bhakti’s rules restrictive. But if we

shift our focus from freedom to love, we will realize that those rules

facilitate the freedom to love. They help us raise our consciousness from

matter to Krishna, thereby kindling our devotion for him and enabling us to

relish the supremely fulfilling bond of love with him. And Krishna doesn’t just

ask us to follow rules — he also offers us his love, and the protection and

liberation thereof. At the Bhagavad-gita’s conclusion (18.66), when he asks us

to devote ourselves to him, he assures that he will protect us from any

untoward consequences. Ultimately, he grants the supreme freedom: freedom from

material existence’s many limitations and miseries. When we practice

bhakti-yoga diligently, he, by his grace, takes us to his eternal abode, where

we can live and love with full freedom.

Tuesday, 10 May 2016

Nothing distracts us as much as we ourselves

We live in a culture of mass distraction. Worldly things

around us try to catch our eye in myriad ways. And with us lie devices that are

potentially universes of distraction. No doubt, in today’s work environment,

devices are often indispensable. Still, even when we are using a device for our

work, we may get distracted on the device itself to social media, net surfing, emails

and what not. We may chat here, read there, watch somewhere else — forgetting

what we intended to do and forgetting even that we have forgotten. Even if we

put our phone in silent mode, disconnect ourselves from the internet and move

away from chat boxes and chatterboxes — all conditions conducive for

undistracted work — we may give in to some wayward impulse and seek out some

distraction. Such incidents show that outer distractions are not as big a

problem as our inner distractibility. Such distractibility stems from our

dangerous inner distractor: the mind. The Bhagavad-gita (06.26) acknowledges

the mind’s restlessness, but still exhorts us to focus it on spiritual reality.

This exhortation implies that we have the capacity to focus our mind. Though

our capacity for mental focus is presently under-developed, we can boost it by

practicing bhakti-yoga. This time-honored yoga links the mind with the

supremely pacifying and satisfying object of thought, Krishna. When we relish

the serenity and joy of absorption in Krishna, we get convinced that we can do

better than wander off wherever the mind wishes to wander. This conviction

inspires within us the resolution to no longer pay heed to the inner

distractor, but to focus on Krishna as our object of service in all our

activities. By this devotional resolution, we gradually get empowered by divine

grace to detect, neglect and reject distractions, both external and internal.

Monday, 9 May 2016

Break people’s misconceptions – don’t break

peopleThe

Bhagavad-gita concludes by urging us to share its message of love with others

(18.68-69). Sometimes, we misconstrue this call to share as a license to go on

the offensive, to break people’s misconceptions for getting them to accept the

Gita. Unfortunately, our overzealousness makes us go beyond breaking their

misconceptions to hurting and breaking them. Thus, we end up alienating them

instead of attracting them. To prevent such unintended consequences, we need to

remember that people are not their opinions. They are souls, eternal and

beloved parts of Krishna, even if they have strong misconceptions. When we

equate people with their present opinions, then, during our preaching, we end

up targeting people instead of their misconceptions. If people sense that an

intellectual discussion has turned into a personal attack, their defences go

up. Even if our strong arguments break those defences, people don’t get

persuaded; they feel even more threatened now that their defences have broken.

So, being driven by a misinformed reflex for self-defence, they come up with

some excuse, however flimsy, for not accepting the truth. Pertinently, the

Bhagavad-gita (03.26) urges us to not disturb people’s minds, but to encourage

them onwards in their spiritual journey at a speed and level they find

suitable. Essentially, we need to see people as partners, not opponents, in the

search for the truth. Of course, some people may stay antagonistic, no matter

how amiable our conduct. If their hostility is unremitting, then we may need to

end the discussion and serve them through our prayers. But frequently when we

change our attitude from inimical to cordial, then we will speak and act,

consciously and subconsciously, in ways that gets people’s defences down. The

more they become more open to the Gita’s illuminating wisdom, the more it

empowers them to overcome their misconceptions.

Saturday, 7 May 2016

There’s no need to be confidently pessimistic

To achieve anything challenging, we need to be optimistic.

Bhakti can boost our optimism by helping us realize that we are not alone;

Krishna is always with us – he loves us and wants the best for us. However,

during our bhakti practice, our mind subtly and sinisterly shifts our focus

from Krishna to the hurdles between him and us: our conditionings. When they

cause us to slip and fall, we become disheartened, thinking, “I can never

overcome these conditionings.” Such a feeling, while understandable, is not

reasonable. How, after all, can we know the future so surely? Have we

mystically developed the power of precognition? No, our confident pessimism

comes not from our precognition, but from our mind’s deception. Our mind is

presently ruled by our conditionings, so it often acts as our enemy. It wants

to keep us in its control – control that is threatened by our practice of

bhakti. So, it takes us away from Krishna by attacking with temptation, and

then keeps us away from him by attacking with pessimism. We may fall to the

attack of temptation, but we don’t have to stay fallen by letting pessimism

paralyze us. Gita wisdom assures us that no matter how strong our conditionings

may be, they are no match to Krishna’s omnipotence. The Bhagavad-gita declares

that even if devotees succumb to misdeeds, they are still well-situated as long

as they keep practicing bhakti (09.30). And by that diligent practice, they

will soon become virtuous (09.31). By remembering Krishna’s omnipotence, we can

replace our confident pessimism with confident optimism. Energized thus, we can

strive to remember and serve him to the best of our capacity. Being pleased by

our sincere endeavors, he will purify us by his omnipotent mercy, gradually

empowering us to rise to levels of freedom that had earlier seemed impossible.

Wednesday, 4 May 2016

Sharing spiritual knowledge is about not just delivery but also discovery

If we are told to deliver something to someone, we may feel

belittled: “I have better things to do than act as a deliveryman.” We may feel

similarly belittled when told to share the Bhagavad-gita by simply delivering

to our audience Krishna’s message as heard in the bhakti tradition. But such

negativity is unfounded because, as regards spiritual knowledge, delivery is

not demeaning; it is illuminating. Delivery stimulates discovery – this is

demonstrated in Sanjaya’s testimony after repeating the Gita to Dhritarashtra.

Sanjay feels ecstatic by meditating on the message itself (18.76) and on the

goal of that message: Krishna (18.77). Extending the delivery metaphor, the

Gita is like a feast that is inexhaustible – the Gita-feast can be relished by

not just those who receive it, but also those who deliver it. Like Sanjaya, we

too can make illuminating spiritual discoveries while delivering the Gita. To

share the Gita properly, we need to take intellectual responsibility for it,

learning to present it intelligibly, appealingly and relevantly for our

audience. And the more we strive to explain its relevance to others, the more

we appreciate its relevance for ourselves. Moreover, as the Gita’s relevance

registers within us, we see this time-honored classic not so much as an

abstract metaphysical treatise as a practical guide for living. Accordingly,

when we share the Gita with this applicational thrust, we understand that our

responsibility is not just to present it, but also to represent it – we need to

live according to its teachings. When we embrace this responsibility to walk

our talk, we start applying diligently the Gita’s central recommendation to

practice bhakti-yoga. By the steady cultivation of bhakti, we make life’s

ultimate discovery: we realize and relish Krishna as the embodiment and

fulfillment of all our aspirations for eternal love and unending bliss.

Tuesday, 3 May 2016

Distraction is an invitation for temptation and degradation

Suppose we are rowing a boat in an area where the current is

going in a direction different from where we wish to go. Suppose further that

the current is moving towards an area of stormy weather. The current will

naturally push the boat in that direction. If instead of rowing diligently to keep

our boat on course, we let ourselves get distracted, our boat will be swept

into the storm. Thus, distraction will turn out to be an invitation for danger.

Similarly, within our consciousness lie certain currents – these correspond

with our various attachments, which are our default definitions of pleasure.

Our consciousness in its innate pursuit of pleasure naturally moves towards the

things we are attached to. If we let ourselves get distracted, the current of

our attachments will sweep us into unwanted actions. And the ramifications of

those actions may become a dangerous storm in our life. Pertinently, the

Bhagavad-gita (02.67) cautions that if we dwell on our wandering senses, we

will get swept away, as wind sweeps away a boat. Just as we can resist the sea

current by rowing purposefully, similarly, we can resist our attachments by

engaging ourselves purposefully. The best purposeful engagement is devotional

service to Krishna because he is the source of the highest happiness, and

bhakti comprises a heart-to-heart connection with him. The more we focus

devotionally on him, the more we relish a higher satisfaction that makes

temptation less appealing. Whenever we feel like becoming lax in our devotional

focus, we can remind ourselves of the danger of distraction – it is an

invitation for temptation and the ensuing degradation. Such reminders will spur

us to absorb ourselves in Krishna. Though attaining devotional absorption may

seem to be demanding, it will be protecting, and it will eventually become fulfilling,

supremely fulfilling. –

Monday, 2 May 2016

Use the modes to analyze, not criticize

For making sense of the world, the Bhagavad-gita offers an

analytical framework centered on the concept of the three modes of material

nature. The modes are subtle forces that shape the interaction between matter

and consciousness. Under the modes’ influence, different people perceive, think

and act in different ways. When we start practicing bhakti-yoga diligently, we

rise to goodness and give up gross sensual indulgences. Our capacity to live

somewhat purely may make us judgmental towards others, especially those living

in the lower modes. We may label them as “foolish, sinful, degraded.” When

people sense our condescending attitude, they become alienated, not just from

us, but also from Krishna. By alienating them thus, we thwart Krishna’s

benevolent purpose of helping them rise. Moreover, our condescending attitude

stems from ignorance – from our ignoring the reality that we too are under the

modes’ influence, even if at a different level. The Gita (18.40) reminds us

that all living beings are under the modes. A PhD student may feel that the

kindergarten level exam is ridiculously easy (“How can anyone be so dumb as to

not get that?”). But that exam is as difficult for a kindergarten student as is

the PhD level exam for the PhD student. Similarly, thinking and living in

goodness may seem like obvious common sense for us. But for those in the lower

modes, rising to goodness is difficult, as challenging as is, say, rising to

transcendence for us. The framework of the modes is meant not to criticize, but

to analyze – to understand who is at what level and to thereby guide them

towards gradual but manageable steps up from where they are. When we thus see

empathically instead of critically, people’s behavior will start making

increasing sense, and we will be able to offer them help that actually helps.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)